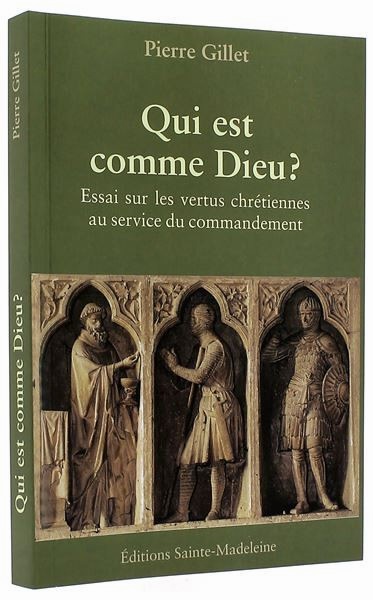

"Who is like God?" (1), the book by Lieutenant General Pierre Gillet, exhaustively inventories the qualities of a leader and outlines the Christian virtues necessary for command. What might seem like a book for initiates, a new TTA (1), becomes, under the delicate and virile pen of Pierre Gillet, former commanding officer of the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment and general commanding the Rapid Reaction Corps – France, a poetry of being, imbued with spirituality, passion, perseverance, and dignity.

“Why does a young Frenchman die in Afghanistan? France, the tricolor flag, no, nonsense! He dies for his buddy, his sergeant, his lieutenant, his colonel. Why? Because when you face death every day, a sacred bond is forged. It's simply called love.” Lieutenant General Antoine Lecerf was declaring the soldier's intention on operations, and his statement was intriguing: love would underpin his actions, in this case, love alone, love alone… Love is born of action, love rests on deeds, as Pierre Gillet reminds us, but also on knowledge, knowledge of souls—we'll come back to that—knowledge of the human condition, because you have to know well to love deeply. Love opens and forms the foundation of this primer and reveals the kind of leader General Gillet wants to tell us about, a leader of the kind that defeatists would say no longer exists because they refuse to see beauty and revel in a disillusioned attitude. A leader knows that for an order to be carried out with fervor, it must contain an element of love. The soldier who does not love will have to learn to love. It is difficult to imagine a truly good soldier consumed by resentment; such a person would endanger the mission. Love demands self-exposure, letting go, taking a risk—and there is, moreover, a reciprocity in action: the leader takes a risk in making a decision, and the subordinate takes a risk in doing everything possible to carry out that decision. Every practitioner of combat sports knows that they are never more vulnerable than when they attack. The centurion, by opening Christ's side, opens his heart, ready to receive baptism. Thus, one must accomplish the mission to understand its full scope. Comfort, if it comes from a mission successfully completed, reinforces confidence in one's leader and his orders. Becoming a soldier therefore consists of transforming "the love of giving into the gift of love.".

The word "vocation" is absent from this primer, yet it underpins the entire text. General Gillet describes vocation, the fulfillment of vocation, "the densification of being," much like the beautiful eponymous book(3) by the Vénard brothers. The soldier's only true obligation: to densify himself, through constantly renewed practice, through self-sacrifice, a taste for effort, through sweat, through the elevation of the soul, through love—always love!—of work well done… There are a few professions that demand and allow this densification: priest, poet, and soldier—"professions" defined by vocation and synonymous with it. The call to densify oneself in order to prove worthy of "one's buddy, one's sergeant, one's lieutenant, one's colonel," of all that matters and is precious to the being who wishes to defend and honor his country, even unto death. Densification is rooted in relationships. Man copies. He needs a model. His adherence must be based on love and admiration. The model must therefore be exemplary. What allows this densification? Is there some kind of magic, some esotericism, to which one must adhere in order to reach this state?

The chapter "Authority and Commitment," a key chapter for understanding the book that follows "Love Like Its Shadow," provides the answer and elevates the reader. The word "authority" has been so decried that its use is avoided; even those convinced of its usefulness prefer to use subterfuge when discussing it. Yet authority represents the cornerstone upon which all command is built, and therefore, first and foremost, self-command. Because it is illusory to think that a leader plagued by multiple demons can command serenely. Authority proves to be the alpha and omega of a well-run life. Without authority, there is no consolidation. Without authority, there is no vocation. Without authority, scattered ideas overlap and create endless confusion. Without authority, Creon exists and becomes legitimate. A historian will come along in the future and analyze how our Western world gradually stripped authority of all meaning, attempting instead a "horizontal authority" that no one will ever envy, so utterly farcical is it. To become who we are, as Pindar said, we must help ourselves a great deal, and receive some support from existing structures: family, school, the army, the state… When most of these structures have also abolished authority, the latent conflict rumbles and advances; everyone will gradually turn on their neighbor, for a scapegoat must be found. Authority is what restrains, what prevents. Authority forms a corset, a limit followed to the letter, for who doesn't want to obey the one they love? Without authority, nothing restrains. Everything is permitted. At a time when the transmission of values is waning, it's worth remembering that the army forged bonds, taught respect for those bonds, and strengthened the ranks of those who dedicated themselves to maintaining them. Of course, it did so through conscription, and one might argue that this wasn't its primary function, since war is fought by professionals. Nevertheless, young Frenchmen often learned about authority when called up for military service. While learning authority is difficult, it's essential not to confuse it with power. Authority remains a great mystery. General Gillet quotes Hannah Arendt, who, in her book "The Crisis of Culture," writes: "If we must truly define authority, then it must be by contrasting it with both coercion by force and persuasion by argument." The German philosopher encapsulated the entire philosophy of Antigone in a single sentence! Authority is not power. Authoritarianism, often confused with originality, is a form of power; it has nothing to do with authority, even if it is founded on and grows from its roots. Authority enables vocation because it provides a framework for thought. Always strive to think beyond oneself, always seek the solution that elevates in order to achieve one's full potential. General Gillet reminds us how history illustrates this higher ideal, this quest for heights, for altitude, to admire and not become complacent, to also gain strength, a strength inherited from the ancients. More Majorum . To be worthy and exemplary. Seeking altitude requires great humility.

The principle of reality governs the leader because the mission depends on its understanding. Should he fail on this point, should he lose himself in his ivory tower, cease to concern himself with his subordinates, act differently from what he advocates, use words emptied of their meaning, it would mean that he has forgotten authority; otherwise, it would bring him back to his duty, it would be the sheath that subjects him to the principle of reality, that dictates conduct and gives him the path to follow at all times. Like a gaze capable of changing at will, shifting from micro to macro and vice versa. The altitude to reach, authority, the macro; The principle of reality, daily life, barracks life, the microphone… Lieutenant General Pierre Gillet likes to point out that a commanding officer who remains in his office and is only seen in the morning when he arrives at the regiment driven by his chauffeur, or at official gatherings—that is to say, always from afar, like a mirage—is certainly missing something. Contact, the intimacy of a glance, that crucial bond that requires nurture, humility, and understanding. Authority and hierarchy structure the life of a soldier. Authority needs only one thing: support. Those who govern us and who still cling to the mad dream of having the people's support should take a look at this book, for it would teach them the power of support and how to cultivate it, and the first rule emphasized remains exemplary conduct.

General Gillet's ABCs fit together like a puzzle. I can say, as a privileged witness (4), that Pierre Gillet had already assembled a large part of the puzzle by the age of 20, when, as a young lieutenant, he arrived in the Legionnaires' pit. It is so common these days to see young adults who are childish, so far removed from their calling and indulging in self-indulgence. Pierre Gillet knew very early on where he wanted to go and the means he would use to get there. He was already developing his character. His experience of this development was already evident. It is easy to believe that a military school trains one for this, but it trains one to strive for it, which is different because theory must be put through the wringer of practice. Pierre Gillet observed others and constantly scrutinized the resources they used and the actions they took. Pierre Gillet possessed a certain understanding of human nature, which in the army is summed up with the expression, "the human condition." He already answered to an authority that structured him and allowed him to have both macro and micro vision, to be close to his legionnaires within his section of the Reconnaissance and Support Company, and to lead them on operations in the Iraqi desert or in Africa. Being a lieutenant in an elite regiment marks the beginning of a life as an officer. Being a lieutenant, in a way, defines what an officer will be throughout their career. The young officer has not yet succumbed to the vice of hiding the weaknesses in their armor, let alone correcting them, and they believe that playing to their strengths will suffice. Arrogance lurks, hidden beneath the cloak of complacency. One can see the leader the lieutenant will become, and one can see the lieutenant a colonel once was. Lieutenant is a defining rank at a defining age; the lieutenant commands on a tightrope, his every move scrutinized by superiors and subordinates alike. This perilous exercise also instills an immense sense of freedom, so well-suited to that age; the lieutenant knows he possesses a weapon for the last time in his career: recklessness. The lieutenant still seeks that coincidence of self evoked by the historian François Hartog(5), a coincidence of the theory that surrounds him upon leaving the academy and the practice of command with seasoned soldiers who are not easily fooled. Pierre Gillet, a lieutenant, had already drawn a precise line between the state of power and the will to power. He did not seek self-affirmation, but self-understanding. The key to this famous coincidence.

There is a duty to practice this self-reflection for those who wish to improve themselves, to add depth, to enrich themselves, to soften tendencies contrary to their calling, to refine, to mortify, to be precise… Self-reflection is not an end in itself, because it can quickly become an egotistical and narcissistic exercise. General Pierre Gillet brilliantly deciphers the various attitudes adopted as so many poses to mask the stains on a soul rather than to cleanse it! Become who you are . There are potentially as many bad leaders as there are bad followers. The author emphasizes the inner life here, which is not surprising for a reader of Dom Romain Banquet's "Conversations on the Inner Life." The inner life aids the leader who surrenders to it. But the inner life is also found in a soldier who already possesses an inner treasure, an existence that has enriched them, that has given them, willingly or unwillingly, a depth useful for carrying out their mission. It goes without saying that the French Foreign Legion teems with remarkable individuals, so full of life experience that each passing day brings a new bonus. The army possesses a valuable asset thanks to this authority to which it submits, an authority that structures each person within a framework where they can express their true selves. There's nothing idyllic here, just an understanding of the individual and the will to provide them with the tools for success in their self-expression. "Attention to subordinates does not contradict the idea that individual interests must give way to the common good," summarizes Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in * Citadel* .

For the reader whose experience with the military has consisted of compulsory and compulsory service, as well as for the younger reader who will likely never wear a uniform, it is important to understand how technocratic and military command differ. This distinction is crucial because the only command our contemporaries are familiar with is often that of the state—the technocratic kind. Military power is always aware of its limitations. “The more precise and realistic the image the leader forms of the future, the more likely it is to become reality.” This quote from André Maurois provides the path to understanding what enables the consolidation that begins with a sense of belonging. The army curbs excess because it undermines this sense of belonging. A soldier knows his mission in the barracks as well as in operations. The same is true for his commander. Only a deep and personal understanding of the mission is possible. This practice has always been central to the army. It may happen that this ingrained practice has been poorly implemented, poorly applied, or poorly transmitted, but it persists because the army relies on its application. The weaknesses and temptations of men cannot change this.

In everyone's imagination, the army represents strength. There are three references to the letter F in General Pierre Gillet's book: loyalty, faith, moral strength… Nothing concerning strength itself. An error? An oversight? Why even mention strength? Soldiers train constantly to acquire self-confidence and reflexes that will allow them to extricate themselves from most difficult situations. Strength is not an end in itself. Knowing one's limitations, seeking what one hides from oneself, striving for freedom in all things—this is the duty of both soldier and leader, for it is clear that their shared interests compel them to embrace a number of virtues together. The author writes: “Without always expressing it, many military leaders believe in something higher and stronger than the mere respectability of the people entrusted to their command. They witness priceless generosity and self-sacrifice, sometimes even at the cost of their own lives.” They know that there is something more than mere material existence and the satisfaction of basic needs, something that drives their soldiers to surpass themselves, to remain faithful to their commitment to the very end. Consequently, they cultivate a high regard for human dignity. Having witnessed concrete manifestations of human greatness, they embrace the idea that humanity is oriented toward "a true realization of its being, that is to say, toward goodness." A leader, if a good leader, enables this transformation by leading their subordinate to accept the proposal, the direction, by correcting poor choices, by showing patience, and by refusing the easy paths and injustices that wound trust. If the men under such command believe in this, these men will reach for the stars. "A human being has roots in their real, active, and natural participation in the existence of a community that preserves certain treasures of the past and a certain premonition of the future." "Is it possible to understand what our era lacks in order to live better? Could it draw upon the military approach, part of its DNA, to understand this? General Pierre Gillet provides a fundamental and masterful answer in his chapter on Freedom: 'Above all, admit that this quest for truth can succeed. Our world prioritizes personal perceptions, feelings, and doubt over critical thinking, autonomy of thought and action over in-depth reflection on freedom and obedience.'"

“There is no wonder but man,” says the chorus in Antigone. The wonder is the freedom that man has received and that his creator has not taken away, despite his shortcomings and infidelities. He has only bound it with death. General Pierre Gillet tirelessly sought to discover this wonder throughout his thirty-year career, these glimmers of wonder in the souls of soldiers, and to encourage them to cleanse what could be cleansed so that they too might see this wonder before their eyes. Anyone who wants to command, even just their own life, where all command begins, must read this book. If the reader finds a common thread with their daily life and a way to better manage it, Pierre Gillet will have contributed. For to the question, “Who is like God?” the answer comes, obvious: those who must imitate Him.

1- Who is like God?, an essay on Christian virtues in the service of command. Pierre Gillet. Sainte-Madeleine Publishing (https://boutique.barroux.org/philosophie-essais/3175-qui-est-comme-dieu-9782372880275.html)

2- TTA, All Arms Text, a collection of general regulations for the French Army.

3- The Densification of Being: Preparing for Difficult Situations. Christian and Guillaume Vénard and Gérard Chaput. Pippa Editions.

4- I had the good fortune to know Lieutenant Pierre Gillet when I served as a lieutenant in the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment; he was the president of the lieutenants' association. We became friends, and that friendship has never wavered.

5- Memoirs of Ulysses, stories about the frontier in ancient Greece. François Hartog. Gallimard Publishers.

Leave a comment