In the middle of a long, drawn-out Saturday morning, the phone rang. A familiar voice spoke impeccable French with a delightful German accent: "Lieutenant, do you think it would be possible to invite a friend, François Lagarde, to the festivities?" I replied that it was no problem at all, and my caller hung up in a flash, as was his wont. I had met Ernst Jünger for the first time three weeks earlier. He still addressed me, with a certain deference, as "Lieutenant." Meeting him in Wilflingen had fulfilled a dream; he had received me with a courtesy that, again, had almost made me uncomfortable, and he had assured me of his presence at the show we were preparing at our rear base for the return of the troops from Operation Daguet in Iraq to Nîmes. But I didn't know François Lagarde, whom the German writer had mentioned, and I could tell from the sound of his voice that this was a wish close to his heart. He told me he lived in Montpellier and would come on his own… Shortly after, I received another call, this time from François Lagarde, who introduced himself on the phone and told me he was a photographer.

François Lagarde had a gentle voice, and I never heard him raise it. At all times, in all circumstances, he remained in control of himself, and it didn't seem like an effort to him. He had this soft, questioning voice, whose questioning served as much to discover as to confirm. François possessed a genuine gentleness, which was not feigned, but he was also inhabited by a certain ferocity that I attributed to the twofold emancipation he was convinced he had achieved: emancipation from his background and emancipation from all forms of constraints, like those who turned twenty in 1968. François was a Protestant to his very core. He rejected this condition and therefore boasted of having rid himself of it, of no longer bearing the weight of his two pastor parents, but he continued to struggle, and deep down, I always thought he was aware, even if he acted like someone who had won, that the fight would always be with him. So he extricated himself from his Protestantism by adopting a Fellini-esque approach, searching for the slightest fragment of pure life, of Dionysian life, of an orgy of life… It was his agony. He never shied away from it. There is something terrible about seeing a man retain only gray, dull memories of childhood… No childlike joy comes to counterbalance this feeling. If everything in life is a matter of perspective, joy should always be the perspective of childhood, because joy felt fully in a pure soul will always seem stronger than the vicissitudes of adult life. Time often accustoms us to our own hypocrisy. And we mistake this habit for a victory. François Lagarde exuded an unshakeable complexity. It was hard not to like him. He was spontaneous, always curious, and radiating a truly Catholic joy. He wouldn't have liked me to attribute a Catholic quality to him, but he would have been flattered, without admitting it, of course.

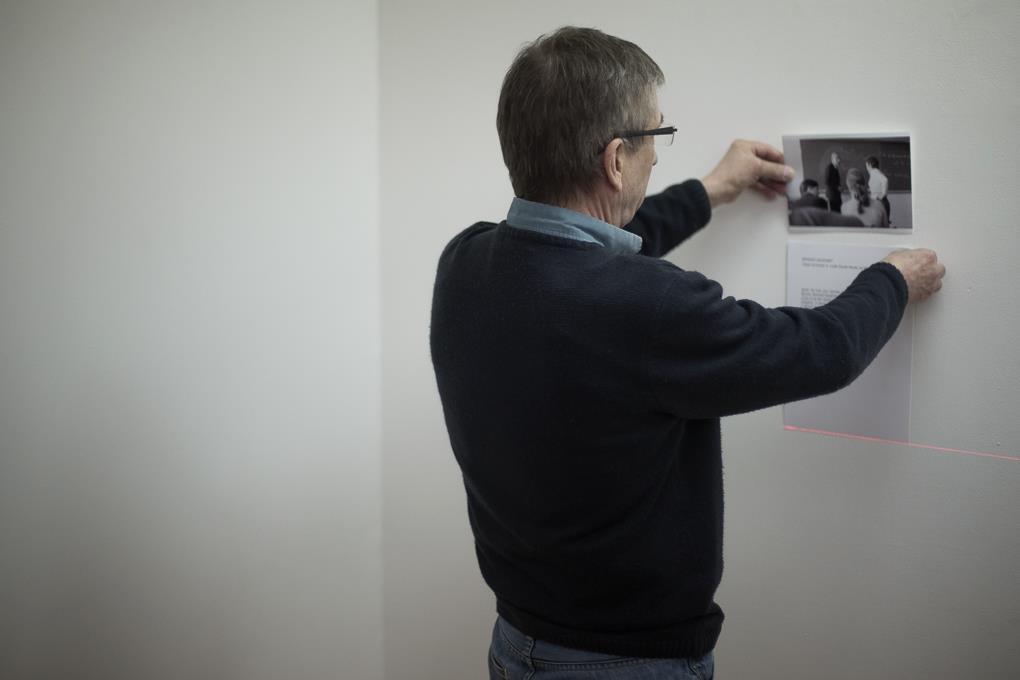

It would take too long to recount our many visits to Ernst Jünger after he allowed us to get to know each other. Jünger possessed this unique sensitivity; he knew people through their souls, and there's no doubt he first forged this vision on the battlefields. A glance was enough. A handshake. When Ernst Jünger shook your hand, it felt like a pact, as if he wanted to bury both hands in the ground to plant a new vow. He knew people beyond themselves, beyond decorum, when the social veneer had been stripped away. And if one believes that the actions of others can have any meaning at all, one understands that an encounter initiated in this way could not fail to have meaning, a profound meaning that would always elude its protagonists. But only here on earth. Jünger had infinite patience. François could take his picture, ask him to move, and he always let himself be moved and complied. Jünger displayed as much ease and patience with discussion and the questions I asked him as he did with the photographs. One day, I understood that Jünger loved human contact, camaraderie, and in that he remained a soldier. And he loved individuality. He disliked anything anonymous and would ostentatiously show me boxes of books sent by his publisher for signing, displaying a distaste for a task he wouldn't perform anyway. He loved camaraderie, that which binds and unites people and reveals them. He loved individuality, of cultures and of people, and that is what he always sought throughout the world in his travels in search of unique cultures and people.

François underwent a major transformation: at a certain point, film took precedence over photography in his mind. He had thousands upon thousands of photos of rock artists, eccentric poets, and complete unknowns… I never saw a bad photograph by François. He always captured something that eluded everyone else. He loved to talk about that fleeting moment, he loved to say that the eye was as much seen as it was seen, basing his discourse as much on Aristotle as on more recent thinkers. He named his film production company Hors-Œil (Off-Eye), and when, at the beginning of this new adventure, he asked me what I thought of that name and two or three others he was considering, I told him I didn't like the sound of "hors-œil" (off-eye), but that it suited him well, and he gave me a smile that spoke volumes. Another time I told him he was doing a bit of Claudel, saying that the eye listened, and he made a face, unsure whether to take it as a compliment. François was a Bergmanesque character, quite unlike Claudel. He had published Albert Hoffman in French and knew LSD inside and out. He belonged to the 70s, but knew how to rearrange them so they would be understood in our time. That's how he juggled a multitude of diverse, varied, and contradictory references that came together as if by magic. His eclecticism knew no bounds. He had taken LSD with William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg and had introduced me to Gérard-Georges Lemaire and Bruno Roy! And so he moved so easily from one subject to another that it was hilarious. You had to keep up with his restless energy, his train of thought. And there was nothing superficial about this ease in embracing new themes; there was an insatiable curiosity, an appetite for life… He loved following in your footsteps, loving what you loved in order to feel, or at least try to feel, what you felt and what brought you so much joy. So much about him was about travel. He would have liked to take every possible journey in the world, every crossing, every voyage… To follow you to the ends of the earth if you would follow him too. And it was so easy to follow each other… One New Year's Eve, we spent almost the entire night talking, him in Montpellier, me in Paris, and clinking champagne glasses from afar. I had taken the liberty of sending him texts by John Paul II without telling him who they were. He read them, but I couldn't ask the impossible of him, and certainly not to become a Catholic. I teased him, however, by pointing out that he had more arguments after he'd met the author of the lines. He still found things to oppose, and that was also one of his defining qualities: he wasn't satisfied, he was stimulating. Once, while we were discussing religion over sparkling wine with Jünger and Liselotte—I had just returned from a delightful day spent with Banine and wanted to talk to Jünger about a statement he'd made concerning Buddhism, whose philosophical aspect he said he admired, that singularity that always invigorated him when he encountered it—François was struck by Jünger's sudden volubility in talking about religions. François, like any good Protestant, felt compelled to clarify that he, as a Protestant, couldn't possibly think that way. I pointed out to him that the negation was inappropriate in his sentence unless it was inherent to the very DNA of Protestantism. He frowned for two minutes. He held no grudges against anyone. The discussion was lively and joyful, without any pretension… But I remember Jünger's dynamism when discussing Catholicism; one sensed in him a profound respect for mystery. And while, at first, I wanted to get his personal opinion on religion and on Buddhism, which he said he was ready to embrace rather than Banine's Islam, which seemed very far removed from his concerns, and to ask him about Catholicism, I realized that Catholicism was not at all part of that discussion; Catholicism was separate. As was often the case with Jünger, I learned as much from him in casual conversation as in one-on-one professional interviews. I reminded François of this episode when we learned of Jünger's conversion to Catholicism at the end of his life.

After Ernst Jünger died, we saw each other less often. We had both changed our lives. But the magic was still there whenever we met. I spent a weekend at his place while I was on assignment in the region. We talked at length again, as we had for over a decade, about his film project on Jünger, "The Red and the Gray." He showed me hundreds of photos, as he had for the past decade, photos of the Somme. He was living through the First World War, he was living through "Storm of Steel." I think he wanted to discover the secret of this survival , written and described by Jünger in his war writings in general and in "Storm of Steel" in particular. He sensed a secret there that he wanted to unlock. He dreamed of appearing in one of the thousands of photos he had taken. He dreamed of an epiphany. And of an apocalypse. With this film, "The Red and the Gray," François had found the work of his life, a project that occupied him for over twenty years. And the title summed up his life: the gray that had haunted him since Le Havre and his childhood, which he thought he had exorcised by creating the magnificent Gris Banal publishing house, and which returned with a relentless rhythm, devouring him in the daily life of the Great War. His daily life. It was also the gray of technology, a lifelong obsession so vividly embodied in trench warfare, where technology overcame man and forced him to crawl without hope; and the red, that flamboyant red, the red of life, of the seasons, of hallucinogenic mushrooms, the red of blood that bursts forth in a final cry, an eternal cry. And so, during that last weekend, we also talked a great deal about the illness he knew I was well aware of, and which he had been facing with courage and determination, but also with anxiety, for some time now. He reverted to his Bergmanesque self in the face of the solitude of his illness. He didn't lose his enthusiasm, even though maintaining it required more effort, and he told me he had almost completed his life's work. And he was on the verge of finishing it. His life was his work. Passion and enthusiasm regularly filled him, and this never seemed to cease. He loved signs more than meaning, and perhaps that's what provoked in him a mixed feeling of bitterness and poetry. But the meaning still fascinated him. He had filmed entire ceremonies of the French Foreign Legion to which I had invited him. He had filmed a very traditional Mass that was dear to my heart and which he had attended regularly, and his commentary was endless. He sensed in tradition an exemplary strength, something impeccable that would never disappear. He was fascinated and voluble when he spoke about it… I wouldn't be giving a complete picture if I didn't mention how much he loved forgiveness, without making it a sacrament. He adored people who knew how to forgive one another. He had encouraged me to read Desmond Tutu's book, "There Is No Future Without Forgiveness." Even though sometimes new adventures took him far away and prevented him from seeing what still existed, François dreamed of forgiveness. Of universal forgiveness. It would have been pointless to remind him that "universal" is the Catholic word in Greek. He died on Friday the 13th, in a final act of defiance.

Leave a comment